If you’ve followed my guitar posts here, you’ll know that I like the All Fourths tuning (E A D G C F) because it imposes a regularity on the fretboard that allows a player to shift chord and scale patterns across strings without fingering adjustments. It’s also a comfortable tuning to explore if you’re familiar with standard tuning, since only the highest two strings are changed: you can reuse any chord or scale pattern that you’ve learned on the lower four strings, which are already tuned in fourths.

I had been cautiously avoiding other nonstandard tunings since switching to All Fourths around a year ago – I didn’t want to spread myself too thin. But a blog visitor recently asked why I hadn’t considered All Major Thirds tuning here, and I couldn’t resist the invitation to experiment. Now, after exploring M3 for a week, I’d like to share some initial observations. (Alexandre, thanks again for the question that prompted this!)

One way to implement M3 is to keep the guitar’s lowest string at E and tune major thirds above that, giving E, G#, C, E, G#, C. This is the 6-string setup recommended by Ralph Patt, who is considered to be the originator of M3 tuning. Notice that while P4 tuning expands the guitar’s range by a semitone, M3 narrows it by a major third (the highest string drops from E down to C), which is why some M3 players prefer a 7-string guitar. And while P4 only requires two strings to be retuned, M3 requires five retunings, which makes it a very different beast from standard tuning.

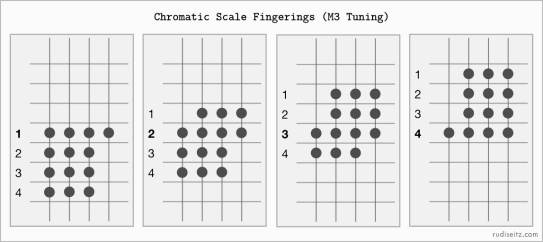

One of the first observations people make about M3 tuning is that you can play an entire 12-note chromatic scale in a span of four frets, with the same finger always playing the same fret, without shifting hand position. Since any octave-repeating scale is a subset of the chromatic scale, this means you can play any scale you want without a position shift or stretch. (If you’ve grown up adjusting to the shifts and stretches of standard tuning, it’s worth taking a moment to consider how remarkable this is.)

A nuance I haven’t seen emphasized elsewhere is that all this holds true regardless of which finger you use for the root note. You can start the scale with your index finger or your pinky, and in each case there’s no need to move your hand or stretch beyond four frets. The diagram below shows four different fingerings of the chromatic scale, corresponding to the four fingers you could use to play the root. The numbers indicate which finger is used to play the notes at the corresponding fret – in the first example we play the root with the index finger (1), in the second example we play it with the middle finger (2), and so on.

Just as the chromatic scale can be played with any starting finger, without a position shift, so too can any scale be played with any starting finger, without a position shift. What’s more, the four single-position fingerings of any given scale bear noticeable similarities to each other, as they are composed of the same building blocks – it’s easy to learn all four fingering patterns at the same time! In the remainder of this post I’ll elaborate on this point with the major scale as an example.

Just as the chromatic scale can be played with any starting finger, without a position shift, so too can any scale be played with any starting finger, without a position shift. What’s more, the four single-position fingerings of any given scale bear noticeable similarities to each other, as they are composed of the same building blocks – it’s easy to learn all four fingering patterns at the same time! In the remainder of this post I’ll elaborate on this point with the major scale as an example.

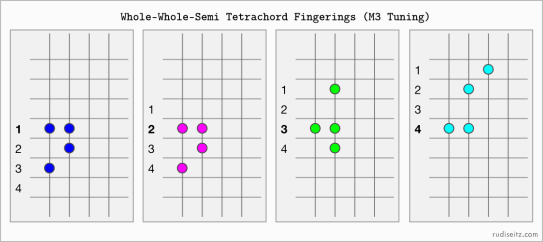

In working out 7-note scales in M3 tuning I’ve found it useful to think of these scales as stacked tetrachords. For our purposes a tetrachord is any sequence of four notes spanning a fourth (alternatively you could think of a tetrachord as a sequence of three intervals that add up to a fourth); here we’ll only look at tetrachords that span a perfect fourth but in a followup post we’ll consider tetrachords that span an augmented fourth. The major scale is nicely regular in that it can be seen as two stacked copies of the same whole-whole-semi tetrachord pattern. Starting at the root, say C, and traversing a whole tone, another whole tone, and finally a semitone gives us C, D, E, F. Starting at the fifth, G, and applying the whole-whole-semi pattern again gives us G, A, B, C. Put them together and you have the entire major scale: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C. The diagram below shows how the whole-whole-semi tetrachord pattern is fingered in M3 tuning, with all possible starting fingers. Notice that the first two examples have the same shape though they employ the fingers differently.

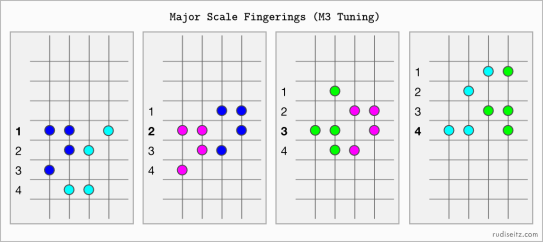

Now we’re ready to finger the major scale itself, not just in one way but in four ways that are interrelated. Since the major scale consists of two copies of the whole-whole-semi tetrachord, each single-position fingering of the major scale can be understood as a pairing of two of the whole-whole-semi fingerings we saw above. Let’s say we want to play the major scale starting with our index finger on the root. First we’d play the whole-whole-semi tetrachord pattern starting from the index finger (I’ve colored this pattern dark blue in the diagrams). Notice how the pattern ends with the second finger playing the fourth degree of the scale. Next we need to skip a whole step up to the fifth degree of the scale, which falls under the pinky. Keeping the hand position fixed and applying the whole-whole-semi fingering starting from the pinky (I’ve colored this patten cyan) completes the scale. What if we wanted to start playing the major scale with the pinky instead of the index finger on the root? The reasoning is similar: first play the whole-whole-semi tetrachord pattern starting from the pinky; then, since the pattern ends on the first finger, skip a whole step up to the third finger and play the tetrachord patten that starts from the third finger (green). The diagram below shows all four fingerings of the major scale as combinations of the whole-whole-semi tetrachord fingerings from the previous diagram:

Now we’re ready to finger the major scale itself, not just in one way but in four ways that are interrelated. Since the major scale consists of two copies of the whole-whole-semi tetrachord, each single-position fingering of the major scale can be understood as a pairing of two of the whole-whole-semi fingerings we saw above. Let’s say we want to play the major scale starting with our index finger on the root. First we’d play the whole-whole-semi tetrachord pattern starting from the index finger (I’ve colored this pattern dark blue in the diagrams). Notice how the pattern ends with the second finger playing the fourth degree of the scale. Next we need to skip a whole step up to the fifth degree of the scale, which falls under the pinky. Keeping the hand position fixed and applying the whole-whole-semi fingering starting from the pinky (I’ve colored this patten cyan) completes the scale. What if we wanted to start playing the major scale with the pinky instead of the index finger on the root? The reasoning is similar: first play the whole-whole-semi tetrachord pattern starting from the pinky; then, since the pattern ends on the first finger, skip a whole step up to the third finger and play the tetrachord patten that starts from the third finger (green). The diagram below shows all four fingerings of the major scale as combinations of the whole-whole-semi tetrachord fingerings from the previous diagram:

Of course it’s possible to conceive of scale fingerings in terms of tetrachords in other tuning systems, but M3 is the only system I know where it works so well – where you can mix and match tetrachord fingerings as we’ve seen to build scales that stay entirely within four frets. In a followup post we’ll take a look at other tetrachord patterns (like semi-whole-whole, whole-semi-whole, etc.) and how they can be used in M3 to finger the natural minor scale, the melodic minor scale, and pretty much any scale you could imagine. ■

Of course it’s possible to conceive of scale fingerings in terms of tetrachords in other tuning systems, but M3 is the only system I know where it works so well – where you can mix and match tetrachord fingerings as we’ve seen to build scales that stay entirely within four frets. In a followup post we’ll take a look at other tetrachord patterns (like semi-whole-whole, whole-semi-whole, etc.) and how they can be used in M3 to finger the natural minor scale, the melodic minor scale, and pretty much any scale you could imagine. ■