In this post I’d like to share a way of thinking about the guitar fretboard that occurred to me when I was revisiting the well-known CAGED system. I had known about CAGED for years, but only recently did it give me an “Aha!” moment.

What I’ll be presenting here is not CAGED itself, but rather a set of observations that were prompted by CAGED. As with anything relating to guitar, someone’s probably thought of it before, but I couldn’t find a similar exposition, so I’m offering my own.

To introduce the basic idea of this post – a certain way of understanding the guitar fretboard – I’ll start with an example involving a different instrument, the piano. Imagine a pianist improvising some music in C major. Say the piano in question is a digital one, and it has a “Transpose” button that lets us uniformly raise or lower the pitch produced by each key on the keyboard.

As our pianist is jamming in C major, we could press the Transpose button to bring each key’s pitch down a semitone. If the pianist did nothing to compensate, the music would abruptly shift into B major. But if the pianist was onto our game, he or she could keep the music in C major by playing everything a semitone higher than before, which would mean fingering the notes of C# major. In this case, the piano’s transposition down to B major and the player’s transposition up to C# major would cancel each other out, and the listener would hear no change.

We could get more devious with our interference, repeatedly setting the piano to transpose up and down by different intervals, but if the pianist knew what we were doing each time, he or she could always find a way to compensate. The pianist might finger the notes of, say, A major, then D major, then B-flat major, so that the music would sound in an uninterrupted C major.

A pianist is not likely to encounter such a scenario where the instrument’s transposition setting is constantly adjusted, but I’d argue that guitarists face this situation all the time. Moving our left hand up and down the guitar neck is, in some ways, like invoking the Transpose feature of a digital piano. Think about it: the fingers of your left hand might stay in the same fixed shape, but as you move your entire hand up and down the neck, the notes you produce with this one shape are “transposed” higher and lower. This concept is so familiar to guitarists that we don’t really think of it as anything special — it’s just how the guitar works.

The familiar transposing quality of the guitar fretboard presents us with essentially the same challenge that our pianist faces as we tinker with the digital piano’s transposition setting. Just as our pianist might have to use fingerings for A major, then D major, then B-flat major to keep the music in C major as the transposition setting is adjusted, a guitarist has to use many different fingerings to keep playing in the same key, say C major, as he or she switches from position to position, up and down the neck. Is there any rhyme or reason to how these fingering patterns relate to one another? Investigating the piano analogy further will reveal that there is.

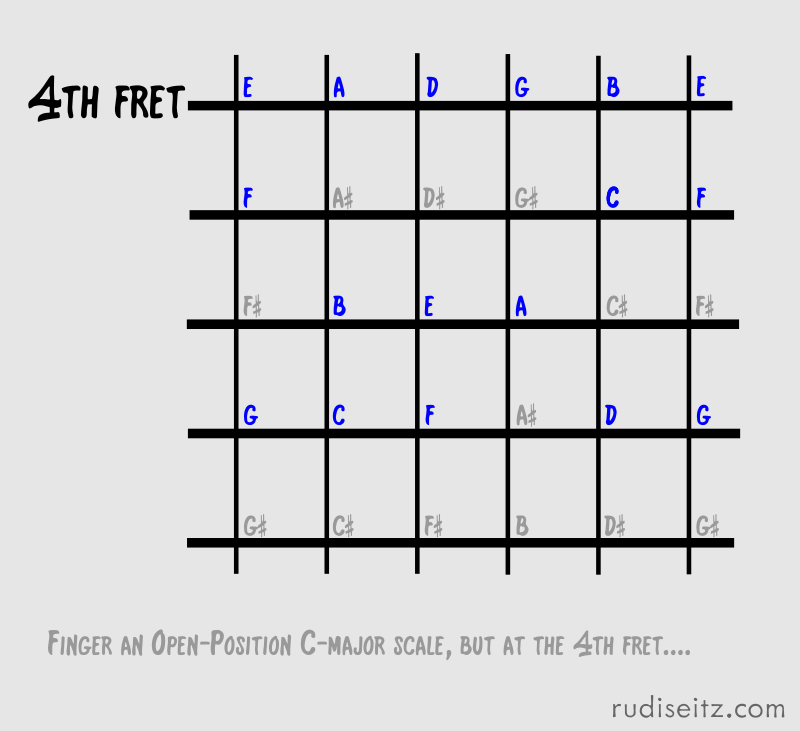

To illustrate this, I’m going to ask you to join me in some experiments. We are going to play in E major in a few different positions on the fretboard. First, put your index finger at the fourth fret on the B string, where it produces a D#. But try something a little unusual now. Instead of visualizing the actual notes in this region of the fretboard, imagine that the notes from open position were superimposed on the area. So, imagine that you’ve got the notes of the open strings E, A, D, G, B, E at the fourth fret, and at the fifth fret you’ve got the notes F, A#, D#, G#, C, F, and so on. If you’re one of those many players who still feels a certain special sense of comfort in open position, even after years of practicing all across the fretboard, try to see if you can bring that same special sense of comfort to the fourth fret while you imagine the notes of open position there:

Now play a familiar C major scale using the imagined notes from open position (blue notes in the diagram below):

Notice that because we’re doing this at the fourth fret, our imagined C major scale actually produces an E major scale (red notes in the diagram below). Great! And just as the CAGED system tells us, we can make a C major shape here, with our middle finger on the second string at the fifth fret, and we’ll get an E major chord.

Now move your index finger down to the third fret. Again, try something a little unusual. Don’t hang on to the notes you were imagining before at the fourth fret. Instead, imagine that all the notes were washed off the fretboard and replaced so that now, there’s E, A, D, G, B, E at the third fret. In other words, just keep imagining that you’re in open position even though your hand has moved and you’re actually at the third fret.

Since you’ve moved your left hand down a fret, all the notes you actually produce will come out semitone lower than before. So then, in order to keep playing E major, you will now have to play everything a semitone higher, in the imagined key of C# major.

In fact, this works out. If you don’t often play in C# major on guitar, you might want to go back to open position and try playing a C# major scale there. Then return to the third fret and notice how the C# major fingering pattern produces the notes of E major. In the diagram below you’re thinking the blue notes (C# major: C#, D#, E#, F#, etc.) and you’re producing the red notes (E major: E, F#, G#, A, etc.).

Now you’ll find that there’s something impractical about this position. You’ve got your index finger at the third fret, where you’re imagining E, A, D, G, B, E, but C# major doesn’t include any of those notes. So, there’s really no good reason keep your index finger there. It’s much easier to play at the fourth fret and imagine C major as we did before. However, if we continue the experiment and move down to the second fret, the situation gets better – it’s just as good as it was at the fourth fret…

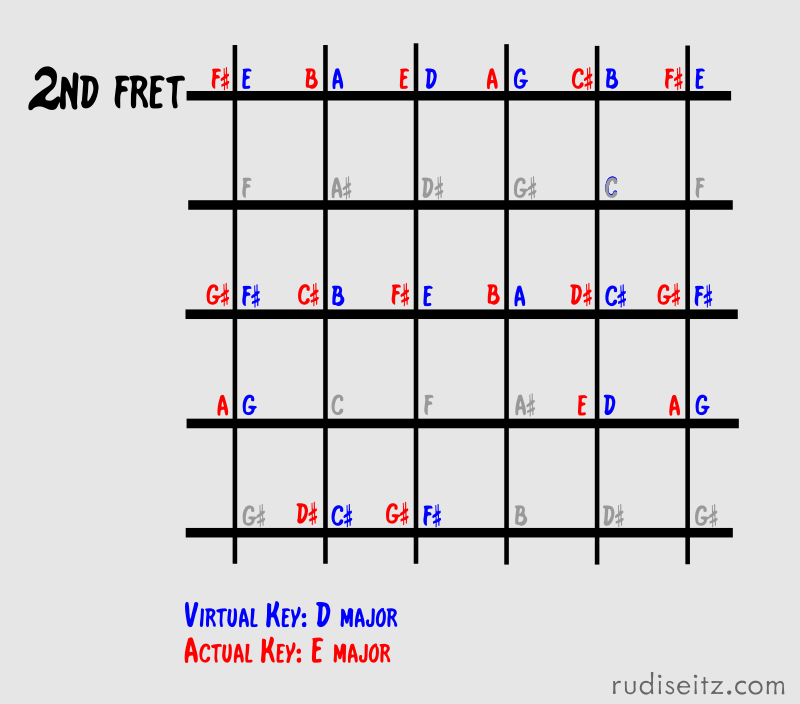

Again then, imagine the notes were washed off the fretboard and replaced so that now, E, A, D, G, B, E fall at the second fret. Since you’ve moved your left hand down another fret, now you’ll have to play in the imagined key of D major (a half-step higher than our previous C# major) in order to produce the same E major. The key of D major uses all of the notes E, A, D, G, B, E, which means that our index finger has a good reason to maintain its position there at the second fret, just as it had a good reason to be at the fourth fret.

In CAGED terms, we could say that we were playing over the C shape while we were at the fourth fret, and we were playing over the D shape while we were at the second fret. Our experiment at the third fret is not part of CAGED per se, but we can still understand the fingering pattern we had to play there as an open-position C# major shape.

So what lessons are to be learned from all of this?

First of all, the CAGED system says you can use the familiar open-position chord shapes all over the freboard. In fact you can go further than that. Whatever position you happen to be at, you can imagine it as open position, with the notes E, A, D, G, B, E underneath your index finger. The idea of “reusing familiar open position shapes” can be extended to “reusing open position itself” anywhere on the fretboard. To play in a certain actual key, you’ll have to play the notes of an appropriate virtual key.

Second, as you switch from position to position up and down the fretboard, you’ll need to use different fingering patterns to maintain the same key, say E major. Each of these fingering patterns for E major can actually be viewed as an open-position fingering for some other “virtual” key. As you move up the fretboard, this “virtual” key shifts downward to compensate for the transposition. Likewise, as you move down the fretboard, the virtual key shifts upward to compensate.

Third, and this will be a bit of a rambling point… when you’re looking at where to position your index finger, you should choose a fret where it will have a couple of notes to play. If you’re playing in E major, the second fret and fourth fret make more sense than the third fret, because there are no notes from E major at the third fret! When you look at the CAGED shapes, you can see that each one of them makes good use of the index finger, because the open position C, A, G, E, and D chords make good use of the open strings.

Place each of the CAGED shapes on the fretboard so that they each produce an E major chord, and then try sounding an actual E major scale “over” those chords. You’ll notice that in order to play the major scale over the A shape, you’ll have to use an open-position A major scale pattern, and to play the same major scale over the D shape you’ll have to use an open-position D major pattern. It make sense: if you’ve positioned the D shape so it produces an E major chord, then the D major scale pattern in that same position should produce an E major scale. Each of these scale patterns includes lots of notes that fall under the first finger.

If we’re looking to expand CAGED to include more positions, we’d want to find chords/keys that use several open strings. Our best bets are F major (five open strings) and Bb major and B major (three open strings) and then perhaps E-flat major (two open strings). These don’t really expand CAGED in terms of fretboard range because the F and E-flat positions will each be only one fret away from E, which is already included in CAGED; the Bb major position will be one fret away from A; the B major position will be one fret away from C. The beauty of CAGED is that it already gives good coverage of the fretboard and doesn’t “need” to be expanded. Still, we’ve added some new options with different patterns, and a new way of understanding what’s really happening when we switch between positions.

Addendum:

Since this is my first guitar post in a while, I thought I’d provide an update on my guitar activities. 2017 was a big year for me in that I went electric. I’ve got a lot more to write about this transition, but for now I’ll just link to a few samples of my electric playing on Soundcloud. I’ve recently completed an arrangement of Danny Boy and an arrangement of Summertime, both for fingerstyle electric. In the few preceding years, I hadn’t been playing very actively; most of my attention was focused on my Canons project. Back in 2015 I did write my first little original composition for classical guitar. Before that I had spent considerable time exploring alternate tunings, including Major Thirds and All Fourths and had written some posts on fretboard concepts including Note Neigborhoods and Guitar Modes Unified. For what it’s worth, I’m now back in standard tuning. I love and still advocate symmetric systems like Major Thirds and Perfect Fourths, but I returned to standard tuning for expediency. Each time I switched tunings, I learned something but also took a step backwards in terms of fluency and familiarity, and since I was constantly swapping my attention with other non-guitar projects, I felt I was getting too scattered; if I wanted to play at all, I finally decided it would be most practical to return to what I knew from childhood. Now that I’ve returned to standard tuning for the time being at least, I’m coming to appreciate its quirks in a way that I couldn’t before, and that’s something I’d like to write about here eventually. ■