My upcoming composition, Canon 94, has an unusual structure. I call it a “reordering canon.” There are two ways to frame this concept. To start out, we need to subdivide our melodic material somehow. We might focus on individual measures, or sections containing some fixed number of measures, or phrases occupying a variable number of measures. Once we’ve chosen a way to subdivide our melodic material, we can describe a reordering canon in either of the following ways:

- It’s a canon that has a leader and a follower, like any typical canon has, except the follower is allowed to rearrange the leader’s material – playing the leader’s melodic subdivisions (measures, or sections, or phrases) in a new order. In this case, the leader’s order is considered to be the original or primary one. We would label the leader’s melodic subdivisions as 1, 2, 3, 4, etc. The follower’s order would then appear as a scrambling of that sequence, like 3, 1, 4, 2.

- It’s a canon where we dispense with the roles of leader and follower. Instead we begin with an unordered set of melodic fragments. Each of the voices is responsible for playing some permutation of the set. That’s to say, each voice must play all of the fragments in the set, but each voice may play them in its own unique order. So one voice might play 4, 1, 3, 2 while another plays 3, 4, 2 1.

The only difference between these two descriptions is that in the first case, we assume that the material has an “original” order (maybe we are working with a pre-written tune). This lets us identify a leader that plays the original tune and a follower that rearranges it. In the second case, the material does not come with any specific order so it’s not meaningful to assign the roles of leader and follower.

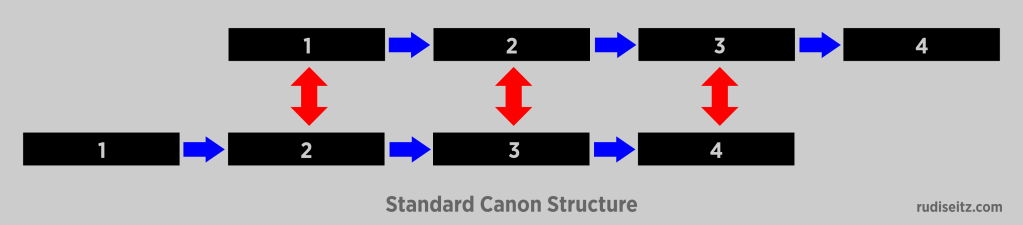

To see what possibilities this idea opens up, and what new challenges it creates, let’s first review how a standard canon works. In a standard canon, the leader and follower play the same material in the same order, but the follower begins after a delay. We hear the follower constantly echoing the leader, always a few measures behind, never catching up.

Here’s a diagram of a standard canon consisting of four sections. I’m using the term “section” to refer to some number of measures – the same number of measures in the canon’s lag or delay. In this case, the bottom line is the leader; the top is the follower.

Look at the arrows. The blue arrows show transitions: section 1 flows into section 2, which flows into section 3, and so on. The red arrows show contrapuntal pairings: section 1 is heard above section 2, section 2 is heard above section 3, and so on. Together, the arrows represent the constraints that make canons interesting, and that make canons hard to design.

Examining the arrows in this diagram, we can see that the inner sections (all but the first and last) have four distinct responsibilities:

- Each section has to make sense coming after the previous section – it functions as a successor.

- Each section has to make sense coming before the next section – it functions as a predecessor.

- Each section has to sound good below the previous section – it functions as a bass line that accompanies its predecessor.

- Each section has to sound good above the next section – it functions as a soprano line that accompanies its successor.

If you understand this, you understand the basic challenge of canon writing.

But not all canons work like this.

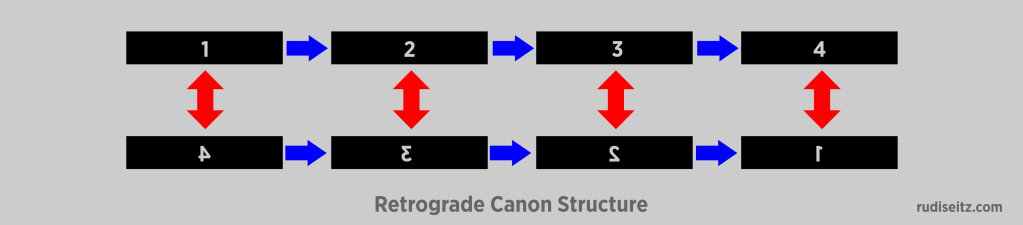

It might seem that an echo – the unmistakable experience of hearing the follower repeat what the leader announced a few moments earlier – is the defining aspect of a canon, but in fact the term “canon” has long included pieces that have no discernible echo. In a retrograde canon, the two lines may start at the same time, with one line playing a reversed or backwards version of the other line’s material. Here’s how that might look:

As we listen to such a piece, we don’t hear a follower echoing the material that the leader had played a moment ago. Instead we hear two contrapuntal parts that may seem to be doing totally different things. In the diagram above, we see that soprano begins with section 1 while the bass begins at the same time, with a reversed version of section 4. We have to wait till the end of the piece to hear section 1 restated in the bass, but it occurs there in a backwards form, which may sound nothing like the forwards form.

If retrograde canons lack an echo, why do we call them canons at all? We call them canons because one voice can still be seen as imitating the other voice. Imitation is key. Imitation is what makes it a canon. The follower’s material is wholly and systematically derived from the leader’s material. It’s just that the imitation here is a complex kind – the imitation involves a transformation, namely reversal.

If we’re going to allow “imitation” to include a transformation as extreme as reversal, and still call the piece a canon, we might ask what other kinds of imitation could be employed to good musical effect. Along with reversal, the standard ones are inversion (turning the material upside down), augmentation or diminution (playing the material faster or slower), and of course transposition (playing the material higher or lower). Those are the ones you’ll find in a textbook, but what else is possible?

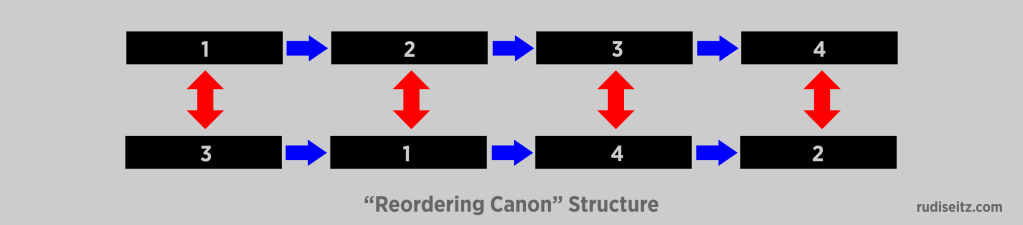

I’ve been pursuing this question in many of my compositional efforts. In a separate post, I will summarize the other nonstandard forms of imitation that I’ve explored. Here, let’s delve deeper into the reordering concept, where the follower must imitate each of the leader’s sections, but the follower is free to change their order. A reordering canon, as I’m calling it, can be visualized like this:

As you can see, where the top line plays sections 1, 2, 3, 4, the bottom line scrambles that order and plays 3, 1, 4, 2. Both parts start at the same time, similar to what happens in a retrograde canon, but this diagram does not show a retrograde canon. Even if the bottom line played 4, 3, 2, 1, it still wouldn’t be a retrograde canon. That’s because a retrograde canon does more than reverse the order of the sections; it reverses all the notes inside each section. We’re not doing that here. The contents of each section are still being played in their regular, forward-moving direction. It’s just that the order of the sections has changed.

Does a reordering canon have an echo? Yes it does, but it’s a more complex kind of echo than we hear in a standard canon. In a standard canon, the echo comes from one part: the follower echoes the leader. In a reordering canon, the echo comes from both parts. That’s to say, some of the sections will be announced first by the bass and imitated later by the soprano; while other sections will be announced first by the soprano and imitated later by the bass. And the delay – the length of time between a section’s initial statement and the onset of its echo – may vary from section to section. In the diagram above, we can see that section 1 is imitated by the bass immediately after it is stated by the soprano; section 3, on the other hand, is only imitated by the soprano after a delay of one section has passed since the bass first announces it.

Is a reordering canon easier or harder to write than a standard canon? In one sense, there are more constraints at play. In a standard canon, any section has only one horizontal context: for example, section 3 would always occur between sections 2 and 4, whether we’re considering the top line or the bottom line. But in a reordering canon, each section has two horizontal contexts. In the diagram above, we see that section 3 occurs between 2 and 4 in the top line; but in the bottom line it serves an opening role and then leads into section 1. Furthermore, each section still serves in two vertical capacities: in this case, section 3 is the bass that we hear below section 1 at the beginning of the piece, and the soprano that we hear above section 4 later on.

By the looks of it, you might think that a reordering canon should be harder to construct than a standard canon, because there are more constraints at play. But there’s one difference that allows a great deal of freedom in how a reordering canon can be composed. In a reordering canon, each section still serves in two vertical roles, but no longer has to serve as the bass to its predecessor specifically and the soprano to its successor specifically; instead, it might be paired with distant sections. For example Section 3 might not have to sound good below section 2 and above section 4; instead, its companions might be Sections 22 and 36! This opens up a lot of compositional options that just aren’t available in a standard canon.

And while it might be challenging to write a sequence of sections that can be played in two different orders (e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 3, 1, 4, 2) there are ways make it work. In my first exploration of reordering canons, I’ve found it helpful to work at the phrase level rather than the measure level. In Canon 94, each section is a self-contained six-measure phrase, there are pauses between the phrases, and I allow for any phrase to be freely vertically transposed. It’s still challenging to write a set of phrases that can sound good in two different orders, but I feel there’s more leeway in how phrases can be rearranged than in how the fragments or gestures inside a phrase can be rearranged. Of course, that depends on the style, phrase structure, and musical materials in use.

We might observe that the traditional contrapuntal operations like retrograde and inversion produce one specific “output” for any given “input” whereas reordering gives the composer many permutations to choose from. Is this too much freedom to still call reordering a kind of imitation, and the resulting piece a kind of canon? The whole reason I’m interested in the reordering concept is because it’s a way to introduce more freedom into canon writing, but I don’t personally think it’s so much freedom that the piece ceases to be a canon. As we’ve seen, there are still many constraints to work with, and one line is still responsible for repeating the other line’s material. If we compare reordering with retrograde imitation, we see that retrograde imitation can completely change the sound and character of a line, including each of its sections, while reordering preserves the sound of each section. Arguably, reordering is less of a drastic transformation that note-by-note reversal, even though there are more ways to do it. ■